Why hurricanes have largely missed Florida’s East Coast — and what it could mean

Why hurricanes have largely missed Florida’s East Coast

Florida is no stranger to hurricanes. Since 1850, at least 178 hurricanes have hit or passed within 100 miles of the state, averaging nearly one per year. But in the last several decades, a noticeable trend has emerged: far fewer hurricanes are striking Florida’s east coast, a shift that has puzzled experts and raised questions about what lies ahead for Central Florida.

ORLANDO, Fla. - Florida is no stranger to hurricanes. Since 1850, at least 178 hurricanes have hit or passed within 100 miles of the state — averaging nearly one per year. But in the last several decades, a noticeable trend has emerged: far fewer hurricanes are striking Florida’s East Coast.

What we know:

Florida has seen 178 hurricanes since 1850, averaging roughly one per year.

Historically, Florida’s Atlantic Coast was a hurricane hotspot. From 1850 to the 1960s, it was struck by 16 major hurricanes, many impacting Central Florida, including the Orlando area.

However, in recent decades, storms striking Florida’s East Coast have become notably rare.

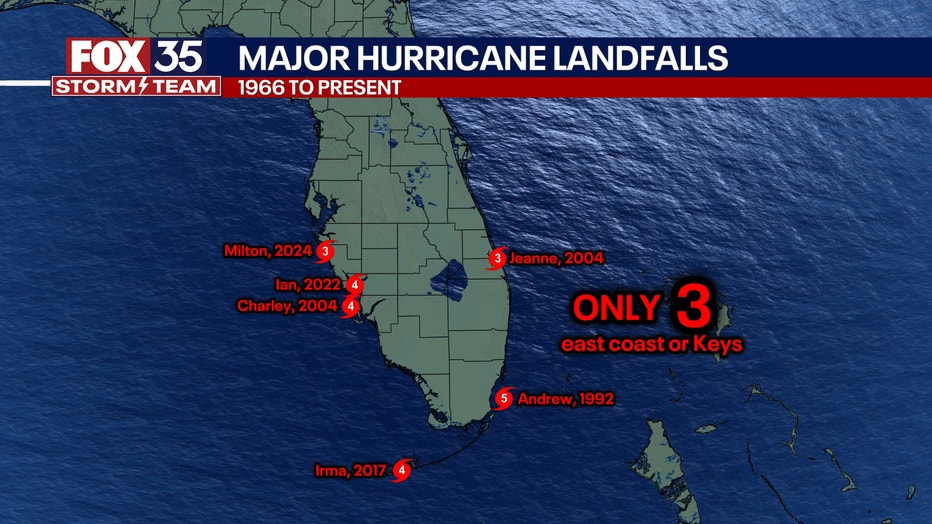

Beginning in the mid-20th century, landfalls on the East Coast slowed significantly — shifting the state’s storm exposure more toward the Gulf Coast. Only three major hurricanes have made landfall on the East Coast or the Keys since the mid-1960s: Hurricane Andrew in 1992, Hurricane Jeanne in 2004, and Hurricane Irma in 2017.

The Gulf Coast has seen a rise in activity, signaling a geographic shift in storm patterns. Experts say this disparity may be lulling parts of the state into a false sense of security. This long-term change in hurricane paths has puzzled climatologists and fueled new research into atmospheric cycles and climate variability.

What we don't know:

Despite data showing fewer hurricanes hitting the East Coast in recent decades, scientists do not fully understand all the forces driving the shift. While atmospheric patterns offer one explanation, experts caution against assuming the trend will continue or that it makes the region less vulnerable in the long run.

Meteorologists stress that long-term weather cycles and evolving climate conditions make hurricane behavior difficult to predict with precision.

What they're saying:

Jamie Rhome, deputy director of the National Hurricane Center, cautions against complacency.

"What I can say is that most people see hurricanes as running on annual cycles — every summer, it’s either busy, not busy, or I’m hit, or I’m not," Rhome said. "But hurricanes tend to run on these cycles of several decades — 20 to 30-year cycles — so what a person experiences can in large part be determined by what phase of this cycle they're in. That’s why you can't necessarily use the absence of storms in the past as a predictor of what’s to come in the future."

Possible theory: shifting atmospheric patterns

Dig deeper:

Meteorologists point to shifting atmospheric patterns as one possible explanation.

For a hurricane to make landfall along Florida’s East Coast, specific weather conditions must align. A ridge of high pressure must be in place over New England and the Mid-Atlantic, while the western U.S. must be experiencing cooler, unsettled weather. That setup prevents storms from curving out to sea, instead funneling them toward the southeastern coastline.

But long-term drought conditions in the southwestern U.S. have altered that balance, flipping the atmospheric pattern and positioning the blocking high-pressure system over the West — where it used to be over the East. The result: hurricanes that once might have slammed into Florida’s east coast are now more often veering into the Gulf or the western part of the state.

While no single factor can explain the trend entirely, experts say it underscores the need for continued awareness and preparation across all of Florida—regardless of recent history.

STAY CONNECTED WITH FOX 35 ORLANDO:

- Download the FOX Local app for breaking news alerts, the latest news headlines

- Download the FOX 35 Storm Team Weather app for weather alerts & radar

- Sign up for FOX 35's daily newsletter for the latest morning headlines

- FOX Local: Stream FOX 35 newscasts, FOX 35 News+, Central Florida Eats on your smart TV

The Source: This story was written based on information shared by Jamie Rhome, deputy director of the National Hurricane Center, and FOX 35 Storm Team Meteorologist Noah Bergren.